Crescent Beach, 2021

Artist Andrew Dadson

STEP AND REPEAT

In 1970, National Geographic published its first Map of the Heavens, a celestial diagram of the night sky constellated with names of the ancient gods. Both the map and map’s title were part of a cartography tradition spanning millennia. Stone carvings that chart the stars date as far back as the second century BC. In Mapping the Heavens from 1693, mythological beings envelop astrological formations from the then-seldom considered perspective of Earth rather than the traditional God’s-eye view. In 2008, the artist Andrew Dadson found himself curious about another cartographic shift—the way the Nat Geo map and contemporary ones like it had begun to change their names.

“After a certain year, they stopped describing the maps as ‘heaven’-related, and they became known as star charts,” he says. “The heavens had been separated from the stars.”

Dadson, who is 42 with a warm, down-to-earth presence, began to collect old celestial maps from wherever he could find them—eBay, booksellers, secondhand shops. Among his purchases was Visible Heavens, a map from 1850. Though Dadson can’t tell you where the impulse came from, he began photocopying the map relentlessly. He made photocopies of photocopies of photocopies, doing this 158 times—once for every year between the map’s 1850 origin and the year 2008.

“Just from repeating the same steps, the map sort of degraded itself and an abstraction emerged,” Dadson explains. The zodiac gods disappeared and the pages became anchored by a large black rectangle enshrined in a swirl of black specks. “A kind of cosmic black hole took over.”

Were you to step into Dadson’s studio in Vancouver, British Columbia, where he works from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday, the first thing he’d do is hand you a copy of Visible Heavens, his book of this work. It’s a black-on-black-on-black hardcover that exists as a physical manifestation of the abstraction. Perhaps more than that, the book has become a kind of manual for understanding Dadson’s approach to painting and creating photographic and installation work.

Andrew Dadson and Blue Wave, 2021

Much of Dadson’s creative process is rooted in repetition. Canvases from his Wave Paintings series are rendered over a period of months with paint that is patiently built up using a palette knife. In Primary Weighted (2021), a smooth white façade covers an eruption of textured color that can only really be glimpsed from the canvas’ periphery. The paint is weighted in such a way that it almost falls out of frame, forming a hybrid painting-sculpture. The effect looks something like beholding an unassuming rock that, smashed open, reveals layers of depth for the eye to excavate.

“In a way, I know what I have to do inside the studio each day,” Dadson says. “It’s like a set of tasks where I have to keep making marks and keep going, but what I don’t know is the end point.” It’s in the ritual of practices repeated over a span of time—painting something over and over again, photographing markings hundreds of times, photocopying star charts—that a kind of transformation unfolds in the work. The ground gives out and things that once seemed subtle or simple or perhaps just mundane, evolve into something more transcendent.

In late summer while his dog Ruby napped at his feet, Dadson took a break from preparations for a group show at the Audain Art Museum in Whistler (Out of Control: The Concrete Art of Skateboarding, through January 8), to discuss his process.

A WORKING ARTIST

Your time at the studio is very much aligned with that of the “working artist.”

Yes, I’m pretty scheduled. I have an 11-year-old, so I do school drop-offs and pick-ups. It wasn’t always like this, but it sort of fits my personality—a studio practice where I’m making something that requires a lot of repetition, a lot of time. Sort of meditative.

What have you been working on this summer? What’s inspiring you?

Since October 2021, I’ve been working on new content for my series Wave Paintings. Here in Vancouver we don’t have very many places to surf. There’s really only Tofino, where I go and spend a lot of time on the beach. The tide goes really far out, and when it’s leaving, there are these ripple impressions in the sand that happen. Sometimes little rocks or shells interfere and make their own pattern. In the studio, I do the same with the paintings. It all starts off with a pencil and a loose wave pattern, then I start applying the paint with a palette knife so it slowly builds up. There might be a mistake, there might be a drip or something—and I kind of just work around it and keep going. There’s always a weight layer, so the bottom is always heavier.

They’re almost evocative of beachside cliffs, the way you can see the passage of time move down the rocks as the sea level has changed.

I often refer to the paintings with geological names because there’s an excavating of the layers in nature, but also in the paintings. Nature is something I’m always thinking about and reflecting back in my work.

Black Medic and Foxtail Barley (Medicago lupulina and Hordeum jubatum) Pink, 2019

Ginestra (Cytisus scoparius) Violet, 2020

White Tree, 2017

What was the first painting you ever made?

It was actually for the Painted Landscapes series, which is ongoing today. In an area that’s under development, I’ll paint plants with paint I’ve mixed myself—sometimes made of milk and chalk, or it might be an indigo. The things I mix up are temporary and once I capture them in a photo, it’s left to disappear. The plants I choose are often the first type of plant to grow in an environment. They’re the weeds, but they’re also the starting point for other plants that can grow after they’ve nutriated and enhanced the soil.

In 2003, I painted my parents’ lawn when they were away—that’s how it started. It was a way of highlighting the space that felt very strange. Everyone had matching lawns, and so I just painted it. The gesture was big back then, but by making the images smaller in the time since—I’ve been able to talk about the idea of urban expansion and development in a more delicate way. That’s what the new ones are. They’re more thoughtful with the plants and working with them. I’ve painted maybe 20 or so different places. For me, as a painter, plants and canvas kind of work together.

How do you choose the place?

The newest one happened in an empty lot in Vancouver. A store had been demolished and what was left was an empty field. When I photograph the plants, they fill the entire frame and the photos are often printed quite big. Bigger than life-size. But if you were to expand the frame of the photo, you’d see that it’s an area no one cares about, and those are the types of spaces that I’m looking for: spaces in transition, forgotten spaces. And the reality is, maybe a month or two after I left, people came in and paved over it.

You never know what’s coming.

Exactly. But it’s part of the development.

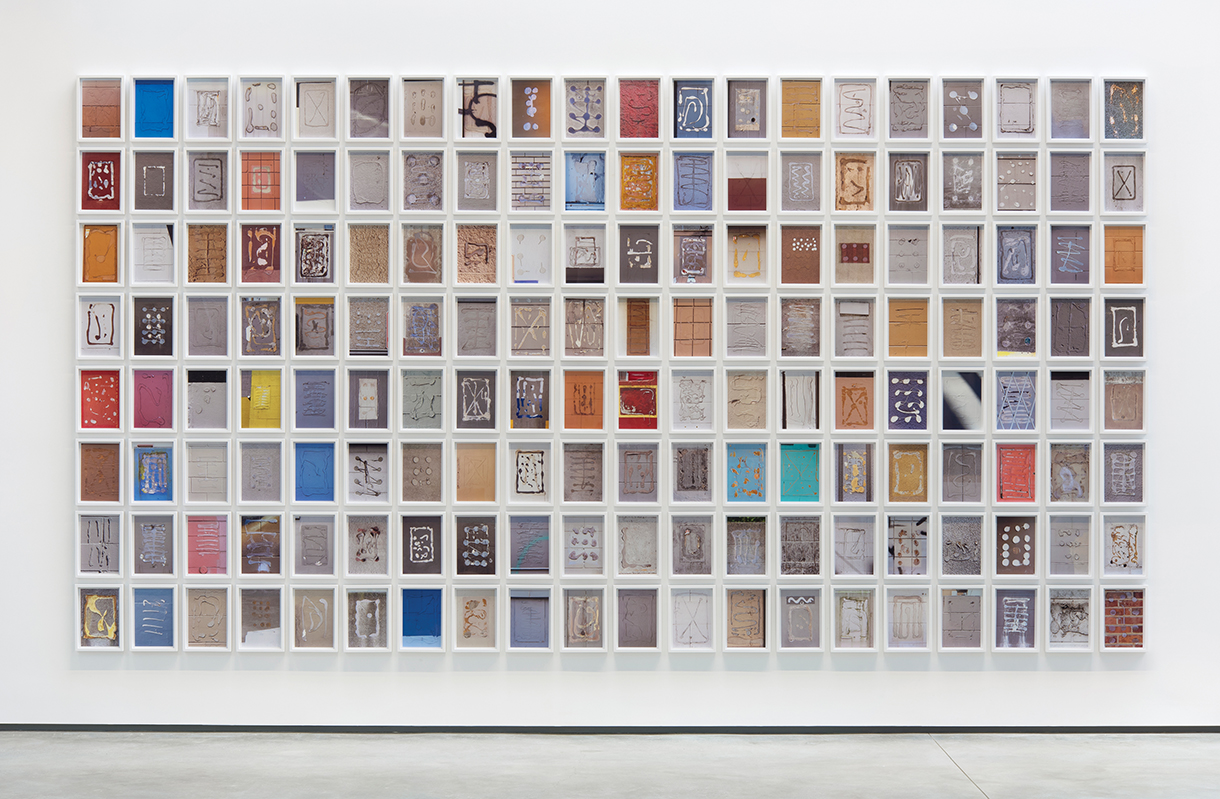

Cuneiform, 2015–Ongoing

Where did your path as an artist begin?

Skateboard culture introduced me to art and artists. I grew up in White Rock, a small town really close to the border of Washington state, and my parents didn’t really go to museums or anything like that. In school, most of my favorite artists were land artists, people interacting with nature. I didn’t get to see Robert Smithson’s work in-person, for example, but those works existed for me in books and I began to think of my own work as functioning like that. The documentation of an action or of a mark-making. As an art student, I was mostly doing installations. Works that were performance-driven that I then documented or photographed.

The group show I’m in next week will have 100 of my photographs, but they’re photographs based around the idea of painting—an ongoing archive of found mark-making that I collect. When people rip down the signs in cities—the No Parking or No Smoking signs, for instance—there’s usually a glue mark that someone randomly made. Once the sign is removed, I photograph the marks and they’ve become a kind of font in a way.

They almost look hieroglyphic.

Exactly. I think of them as something that could spell something out, except they’re missing what they’re supposed to be saying. The sign is gone. So you don’t know what the rules are, how to interact with the city. I find it funny that no one writes their name or even a swear word. It’s very much about the squiggle and you start to see a pattern. Everyone has a type of gesture that they do. I’d be curious to start collecting them in Korea or Japan, somewhere where there might be a whole different set of mark-making techniques.

David Hockney moved from California to Normandy, France, a few years ago, and spoke of the way the change of environment hugely affected the work. It was a case of “environment is everything.” Is it the same for you?

In Vancouver, we have 10 months of rain—so . . . [laughs]. We have different cycles of nature that affect how I think about plants. I can’t work on the photos for most of the year. It’s only in the spring and summer that this kind of work even becomes possible. That’s when the plants start growing from the cracks in the empty lots.

You gratefully acknowledge that you live and work on unceded, traditional, and ancestral territories of the Squamish, TsleilWaututh, and Musqueam First Nations groups. How, if at all, does that influence the work?

It’s really important for us here to acknowledge the unceded territories we work on. I do feel the work I’m doing is always a response to the nature, the place I’m in—whether it’s the empty lot, the beaches, or the neighborhood. The studio area I’m in now is a high-drug-use, lower-income area of Vancouver called the Downtown Eastside. We had a big homeless camp in the park across the street that came up during the pandemic. The city wanted the campers gone, which really just pushed their tents to different areas.

We just received a grant for starting an art tent in the park. It’s going to be a low-barrier, no sign-up art school where people can drop in, make art, get supplies, and leave. We’re bringing a tent back, but want to offer positive opportunities for relaxation, meditation, and making art without any kind of barriers. We’re trying to work with the community and it’s been really rewarding so far, but we’ll see how it goes.

White Re-stretch Violet/Blue/Green/Yellow/Orange/Red, 2013

The work you create requires so much time. It’s this sort of slow and patient process. It’s also a product of the archive—a collection of symbols that emerge from discarded objects in your environment. After decades of work on the same series, has your perception of time itself shifted?

I don't know if I think of time much differently in that way. For me, it’s really about how time and distance can change the way you see something. The restretch paintings I do are an extension of this—they’re almost exactly like Visible Heavens for me, but in a different form. I’ll build up these mountainous blobs of paint on the side of a canvas that I’ve stretched with extra material left around the back. lt’s months of layering. I build it up to the point where you can’t see any unpainted canvas. Once it’s dry-ish, I get a bigger stretcher bar and re-stretch the canvas onto the new stretcher. Even though the painting has stayed the same size, I’m left with a border that’s unpainted. The only thing that changed was the support structure. And to me, it’s like life—one area is being affected, but it’s connected to something bigger that had always been there.